As Black History Month 2021 draws to a close, I’d like to conclude it with a memorial piece that I wrote about my best ever athlete, Albert Hood. I wrote this piece in 1994 shortly after his tragic death. He left an indelible impression on me and I’m sure he influenced and inspired the fans he had in the American weightlifting community. What an experience it was to coach such a competitor!

Springtime, 1981 and the world was a beautiful place. Never mind that Interstate 5 was the world's most boring highway. I-5 was several hundred miles of straight concrete and asphalt that extended from Bakersfield, California through the boring farmlands of the Central Valley to the offramp at Pacheco Pass Road that would lead to the backdoor of Gilroy, the self-proclaimed Garlic Capital of the world. My 1976 Ford Granada was smoothing out the bumps, and the car stereo was performing admirably by pumping out the sounds of the numerous Frank Zappa tapes that I'd brought along to reform the air molecules.

Keeping me company on this trek to the National Weightlifting Championships was Albert Hood, my latest "find" and as I was to eventually realize, the most talented lifter I'd ever coached. We were two happy guys out on the road, looking for adventure. Albert had recently overwhelmed the competition at the National Juniors, setting a national junior record and qualifying for the Junior World's Team. He was on his way to his first nationals and expected to win. Because of Albert's successes, a few people began to think that I might actually be able to coach. The prospect of more success made for a drive full of anticipation.

Of course, Albert had ridden with me to several meets by this time and knew of my fascination for Frank Zappa. He had actually gotten to appreciate Frank's music, a far cry from his normal preference for music more suited to break dancing. The boring miles of I-5 melted away as we combined on vocal duets to accompany You Are What You Is, Illinois Enema Bandit, and Maybe You Should Stay With Your Mama.

On December 4, 1993 Frank Zappa died of prostate cancer while I was at the Americans in Marin.

On September 1, 1994 Albert Hood died of a gunshot wound to the back as he was being robbed in Monroe, Louisiana.

Within a span of less than a year two of the people who had provided foci to my universe had been taken away. They would never walk the face of the planet again. I have to think about this! As we progress through life on this planet, a journey from birth to death, the grim reaper robs us of individuals who provide remarkably unique experiences for us. Some people experience these losses at an early age, and the traumas themselves are frequently life altering. Others, like myself, are fortunate to benefit from having been touched by the uniqueness of these individuals who affect our lives and are enriched because of that touching.

Allow me to expound briefly on the influence of Frank Zappa (I know that this is a weightlifting publication, but I don't think that Bob has any hard and fast rules about the scope of its necrology). Frank Zappa is probably unknown to a great many of the weightlifting community, but those that find his name familiar are probably aware of him solely as the purveyor of Don't Eat the Yellow Snow and Valley Girl. What most don't realize is that his total formal education consisted of a semester's work at Antelope Valley Community College, and yet his compositions were meritorious enough to be performed by the London Symphony Orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Pierre Boulez's chamber music orchestra, and the Ensemble Modern of Frankfurt. In 1992 he was honored by the German music community as one of the three greatest composers of the 20th century. Now I don't know the first thing about formal music, but it was Zappa's attitude that provided a focus for me. He was frequently quoted as saying, " If I like it, I put it out. If someone else likes it, that's a bonus!" His intellectual independence has provided me with a role model, if you will, on how to deal with weightlifting philosophy during my coaching career. I am saddened by his death and the realization that he will no longer provide me with insights. His influence upon my thinking has been significant.

Albert Hood's influence on my weightlifting life has been immense. Most weightlifting coaches in this country labor away anonymously. Our capricious non-system of recognizing coaching excellence primarily acknowledges the finding of talent rather than its development. One coach might achieve reasonable esteem simply because he was able to locate a talented individual. Another coach with equal amounts of perseverance, intelligence, and good intent might be doomed to a lesser level without the good fortune to happen upon a talented individual willing to enter the sport. Albert's talent and great competitive heart provided the perception that I needed to gain entree into the small circle of coaches that might "know something".

My personal appreciation of Albert, however, certainly extends beyond what he provided for my coaching career. The talent provided him by parents Albert, Sr. and Jeweline Hood provided me with an insight into the possibilities that were available in the coaching of athletes. His wonderful good nature and fighting spirit made me appreciate the qualities of great athletes that can neither be coached, nor developed. He also reinforced in me the wonderful times that can be realized in the athletic arena, and the excitement that can be shared by a coach and athlete as they embark on quest after quest.

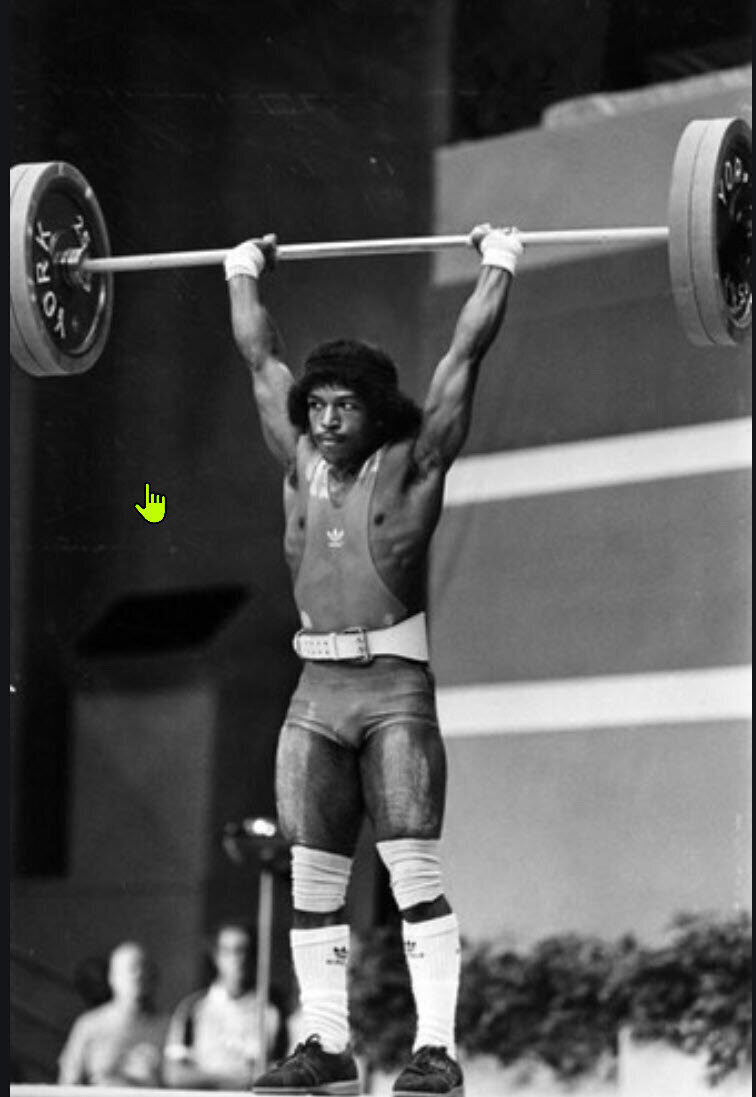

It's just over 10 years since Albert electrified the audience at the Los Angeles Olympiad with a performance that produced 2 national records and an 8th place finish. Anticipation had run high for the performance of our athletes as the Summer Games returned to American soil for the first time in 52 years. Media coverage was ferocious, and at times, stifling. Our weightlifting team was expected to perform well in the absence of the Eastern bloc nations who had decided to boycott. Despite the best of intentions, only three U.S.A. national weightlifting records were set, and Albert authored two of them. The snatch record of 112.5 was the second double-bodyweight snatch ever performed by an American. That lift along with his 242.5 total were permanently retired on December 31, 1992 precipitated by the change of bodyweight classes. I am proud and happy that Albert's records will live in perpetuity, and feel fulfilled that I had some small hand in the establishment of this small bit of weightlifting history.

How could you not love a little guy who one day won the national championships, and the next day spent time showing local York, Pennsylvania youngsters how to break-dance? How could you not love a little guy who upon sighting William Shatner waiting to film a scene for T.J. Hooker in Van Nuys, explain to his brother, "Homeboy be Captain Kirk!"? How could you not love a little guy who once told his team mates that his main goal in life was to be tall? How could you not love a little guy who was unfazed at the Sao Paolo Jr. World's when appropriate equipment was not provided by an official who absconded with the finances, and still set national junior records by lifting on a borrowed bar and metal plates? I could not not love him, and the same could be said for the throngs of youngsters who used to crowd around him during his rise to prominence from 1981 to 1984.

Last week I delivered the eulogy at his funeral. Albert had died shortly after his 30th birthday, a victim of a robbery homicide. Nowhere in the coach's manual can I find a section dealing with the burial of one's athletes, of one's friends. Al, Sr. had laid that responsibility on me when he found that none of the family members or friends felt that they could ever get past the second word. As I spoke I looked down from the pulpit and saw the legs of three of Al's children dangling in the pews as I was transported back to the days when I first saw his legs dangling from a chair in my homeroom and surmised that he might have a future in weightlifting. Just as in 1987 and 1991 the members of my club had expected Al to reappear in 1995 and declare his candidacy for the next Olympics. It won't happen, now.

A big part of me jumped into the burial vault with him. Li'l Al can't hear me now, but I can still say "thanks". Thanks, Al, for some of the best times ever. We were pretty good together, weren't we? The world was a great place! Good-bye, Al. I love you.